This story begins somewhere in southern England, though we don't know precisely where. It is the most likely scenario for the orgins of our Dibble family, but parts of it are pure conjecture. I want to keep the narrative focused on the story, so you won't find detailed explanations of my reasoning, or much about my sources, here. That's what footnotes are for, and there are links to several of them on this page. Feel free to explore.

A man named Robert was born somewhere around 1585, probably in England's "west country". His surname is spelled in various records as Dibbell, Dible, and Deeble. "Deeble" is the spelling most genealogists know him by, so that's what we'll use.

By early 1611 he had at least three children, for whom we have only baptism dates from St. John's, a Church of England parish in Glastonbury, in the county of Somerset, which is just across the Bristol Channel from Wales. These children were John (1605), Johana/Joanna (April 16, 1609), and Frances (February 17, 1611).

He probably moved to Devonshire County sometime after that, because his son Thomas, probably born in 1613, was probably baptized there in April of that year.

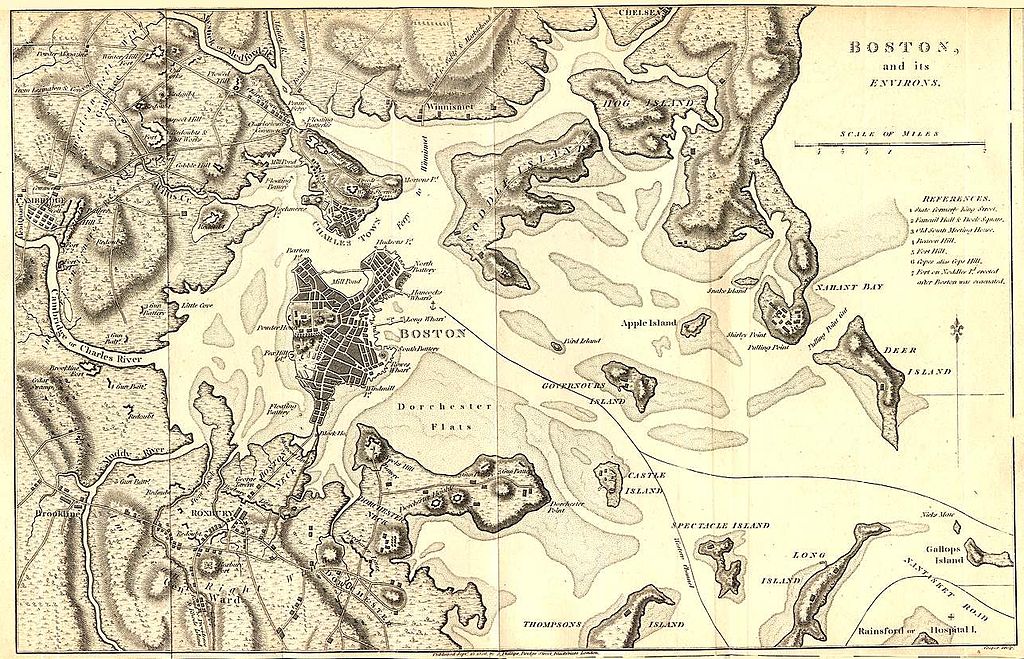

The first organized group of English settlers in Dorchester, Massachusetts, landed on a narrow peninsula jutting into Massachusetts Bay. It was called "Mattapan" or "Mattapanock" by the people who lived there in May 1630. Various translations of this name are given, including "a good place to be", "a good place to sit", or "an evil, spread about place". Today it is known as Harbor Point in Boston.

Captain John Smith, husband of Pocahontas, stopped there briefly in 1614 and bought some furs, and he said that the French had been there on the same sort of shopping expedition before him. In fact, Europeans had been fishing off the Maine and Massachusetts coasts, and trading with the people who lived there, for many decades before large-group organized settlement began. Some of these traders and fishermen set up housekeeping locally. The first permanent European settler recorded by name in the area was David Thompson, who set up on the island that bears his name, about a half-mile off the point. The names of the others have not come down to us. But by the 1620s, Massachusetts Bay was well-known in the West of England, where, along with the religious fervor, something of a "gold rush" mentality had been developing.

Then, on May 30, 1630, the Mary and John, out of Plymouth, England with some 140 Puritan passengers, hove into view off the point and dropped anchor.

Their voyage was organized and partially funded by John White, the rector of the Holy Trinity church in Dorchester, Dorsetshire, England. White, who never left England, was considered a "conforming Puritan", that is, a Calvinist who was willing to work within the hierarchy of the Church of England. Although he was a moderate reformer, he encouraged people to emigrate to New England for religious reasons. He obtained the patent from King Charles I that established the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and it was his followers who sailed to what became Dorchester, MA, on the Mary and John, one of the ships of the Winthrop Fleet. Settlers from the fleet established not only Dorchester, but Boston, Roxbury, Weymouth, and other towns around the bay. It is likely that not everybody in the fleet was emigrating for religious reasons though; some people clearly were looking to strike it rich in the fishing or fur businesses.

Apparently it took these people some time to figure out what to do next, because it wasn't until June 17 that they landed in Mattapan and established the town of Dorchester.The settlement was supposed to be temporary. They were planning to live on the banks of the Charles River, so they didn't plant any crops in the area. But many of the immigrants became sick, and some began to starve, and an emergency relief ship was sent to Ireland for supplies. It wasn't long before the Charles River idea was dropped.

The group's spiritual leaders were preachers named John Maverick and John Warham. Their civil government arrived on one of the other ships, in the person of John Winthrop, first Governor of Massachusetts Bay. However, the local government remained largely in the hands of the preachers and two Magistrates, because the rest of the population were not eligible to participate.

In order to vote, own land, or take part in town meetings in New England in those days, one had to be an adult male "freeman". This doesn't just refer to the fact that many settlers came over as indentured servants.

In the United States, schoolchildren have often been taught that the early settlers of New England came primarily to obtain "religious freedom". In later grades it is sometimes revealed that the settlers were only looking for freedom to practice their own beliefs; they were not interested in extending "religious freedom" to people who did not think exactly like they did, and they enthusiastically persecuted those people as unpleasantly as the English authorities had persecuted them.

But the history is more complicated than that. Even the very strict and peculiar religious group known as "The Pilgrims" were required by the terms of their contract with their financiers to bring people who weren't members of their sect to the Plymouth colony. And although religion motivated many of those who came in the great wave of settlement beginning in 1630, including most of the organizers of those settlements, it was not everybody's reason for coming.

However, in those days, the notion of the separation of church and state didn't exist. The dissenters only had the idea that if you wanted to have a different kind of church, you needed to set up your own state. Within that state, the top officials may not have had formal clerical credentials, but they operated according to semi-religious doctrine. And at lower levels, while a parish priest didn't necessarily have civil authority, his parish did. It was the local unit of government (sometimes called "civil-ecclesiastical" parishes by historians), and it was responsible for keeping records. Conventions of religious morality penetrated deeply into civil and criminal law and procedure, and this was considered normal even by people who were by no means religious zealots or even serious believers. Separation of religion and state only arose as other people arrived who wanted to practice different beliefs and nestled cheek-by-jowl with the intolerant earlier settlers. It remains the only effective means by which different religiously intolerant groups can live together.

So the concept of a "freeman" had both civil and religious elements. Every male who came to settle in the colonies, as well as male children when they reached the age of adulthood, were watched closely by the leadership and if their attitudes and behavior were judged appropriate, they would then be made freemen, an event that was usually recorded in the church records. Beginning May 18, 1631, being a member of a church became a requirement for freeman status throughout the Massachusetts Bay colony.

The first two pages of the Dorchester records are missing, but it seems that some months prior to that date there may have only been seven or eight freemen in the town. However, there were enough in May 1631 to begin regular meetings of "the plantation" to manage the community's affairs. In October 1633 the town government was formally organized, with twelve "selectmen" appointed to meet weekly, a majority of whom would constitute a quorum to conduct business. But all of the freemen were encouraged to attend these meetings, where they all would have equal votes.

Here is how a man named Wood described the town in 1633:

"Dorchester is the greatest town in New England, but I am informed that others equal it since I came away; well wooded and watered, very good arable grounds and hay ground; fair corn-fields and pleasant gardens, with kitchen gardens. In this plantation is a great many cattle, as kine, goats, and swine. This plantation hath a reasonable harbour for ships. Here is no alewife river, which is a great inconvenience. The inhabitants of this town were the first that set upon fishing in the bay, who received so much fruit of their labours, that they encouraged others to the same undertakings."

This is the town Robert Deeble found when he stepped off the Recovery in May or June of 1633/4.

Wanderlust and the "westward, ho!" spirit seem to have gripped some of the early settlers almost immediately. Just about the time when Robert arrived, some intrepid people from the neighboring colony of Plymouth, founded in 1620 by a religious sect known in the United States as "The Pilgrims", were setting up a trading post over 150 miles southwest of Dorchester, on the "Great River" (now called the Connecticut River), at a place that came to be the town of Windsor, CT.

The middle-aged Robert quickly prospered in his new home. He made freeman on May 6, 1635, after which he almost immediately acquired some land.

The earliest English colonies operated on an initial grant of land, sometimes called a patent. Those in charge meted out portions of this land to settlers, called lots or pales, apparently without expecting payment. On December 17, 1635, it was "ordered, that Robert Deeble shall have in lardgement of Two goad in length from his house upward."

What this means is open to question. A goad, when used as a measure of length, has been defined by some sources as 1.5 yards, and by others as the same as a rod, or 5.5 yards. The term is also used as a measure of area, when it means about a quarter of an acre. A traditional acre is supposed to be one furlong (220 yards) long by one chain (22 yards) wide.

So one of Robert's boundary lines was moved either 3 yards or 11 yards (or maybe 440 yards or 44 yards), outwards, and we don't know what size his original lot was, so we don't know how much additional land this brought him. The lots assigned to the original settlers in 1630 were a half-acre each, but Robert was not an original settler.

Less than a month later, on January 4, 1636, Robert was awarded even more land: "It is ordered, that the p'tyes here under written, shall have great lotts at the bounds, betwixt Roxbury and Dorchester, at the great hill, betwixt the sayd bounds, and above the marsh as foll. not to inclose medowe. ... Robert Deeble & his sonne 30 acres"

Robert's son was young Thomas, who probably arrived with the "Hull company" of religious dissenters. Although the date of his arrival is no more certain than that of Robert's, it is clear that they came on two different ships.

The Reverend Joseph Hull was a dissenter who seems to have been a follower of Rev. John Warham, one of the two preachers who came on the Mary & John with the original settlers of Dorchester in 1630. Soon after arriving in New England, though, Hull was fired by his congregation for being "too liberal". He wandered from church to church after that, and Dorchester's early historians do not mention him. It has been said by later historians that Hull, Massachusetts, was founded by this group. It's nearby, but clearly not everybody in the group stayed there.

Meanwhile, word had come up from the settlement at Windsor that the rich river bottom land there was better for farming than the rocky soil of Dorchester. Along with the word had come an abundance of valuable furs, obtained by the Plymouth traders from the locals. Almost immediately some people began campaigning for a move to Connecticut. Among them were the Dorchester spiritual leaders, Revs. Warham and Maverick. Others apparently included some disgruntled local politicians who had feuded with, or run against, Governor Winthrop. There was much contentious debate for and against the move. The "subject agitated the people of the Bay to such a degree that a public fast was appointed, September 18, 1634." People from Dorchester began trickling individually and in small groups out to Windsor, and by the summer of 1635 a sizeable number had settled there. Then in November, a group of about 60 people, with their animals, made the arduous journey. The winter of 1635-36 was terrible for them. Almost all of their animals died, and a few of them struggled back through the snow-covered wilderness to Dorchester. Others, facing starvation, went downriver and took refuge on a ship anchored at its mouth.

But agitation for emigration continued, and the local leaders grew alarmed. They began offering land grants to those who agreed to stay.

At the same time that Robert's lot was enlarged by 2 goads "in length", in December 1635, the town authorities ordered that "his sonne T[homas] Deeble shall have six goad next him to goe with a right lyne up from the pale before his house, on condition, for Thommas Deeble to build a house there, within one yeere, or elce to loose that goad graunted him." Since "in length" doesn't appear in this order, we can assume that "goad" refers to a unit of area--a quarter acre. So Thomas got 1.5 acres at this time.

It is also possible that gradually growing dissension in the Dorchester church contributed to the urge to move. According to Governor Winthrop's journal, there seem to have been doctrinal disputes in the spring of 1636. Some members of the congregation "had builded their comfort of salvation upon unsound grounds, viz., some upon dreams and ravishes of spirit by fits; others upon the reformation of their lives; others upon duties and performances, etc.; wherein they discovered three special errors: 1. That they had not come to hate sin, because it was filthy, but only left it, because it was hurtful. 2. That, by reason of this, they had never truly closed with Christ, (or rather Christ with them,) but had made use of him only to help the imperfection of their sanctification and duties, and not made him their sanctification, wisdom, etc. 3. They expected to believe by some power of their own, and not only and wholly from Christ."

As these arguments were developing, Reverend Warham assembled a large party of Dorchester's early settlers and led them successfully to Windsor, where he established the first church there. His motivations do not seem to have been entirely religious; he also built the first gristmill in the town.

It may be that the additional grants of land to Robert and Thomas were made as inducements for them to stay in Dorchester. Both did, at least for a while. But these enticements were not very successful overall; in the end, about half of the inhabitants of Dorchester moved to Windsor. That included Thomas; although he made freeman in Dorchester on May 17, 1637, he next appears in Windsor, where he was granted freeman status in April 1640.

Was there an argument between Robert and Thomas about this? Perhaps.

Reverend Maverick having died (some say in Boston, though he was buried in Dorchester; the towns were a few miles apart and they, and Roxbury, which lies between them, are all part of the city of Boston today), after Reverend Warham left, the remaining Dorchester church members orchestrated a determined campaign to get the Reverend Richard Mather (ancestor of Cotton Mather, of Salem witch trial fame), to take over. Mather said, "They pressed me into it with much importunity, and so did others also, till I was ashamed to deny any longer, and laid it on me as a thing to which I was bound in conscience to assent; because, if I yielded not to join, there would be, said they, no church at all in this place, and so a tribe, as it were, should perish out of Israel, and all through my default."

Even so, Mather held out until the remaining members of the church agreed to a new covenant to settle the doctrinal disputes and put all of the members of the congregation on the same path to salvation. Robert Deeble signed this covenant along with many others on August 23, 1636. Thomas did not. Much has been made of this fact, but Thomas was not yet a freeman, and it may be that he simply would not have been allowed to sign an official document at that time.

However, included with the pages of a letter that a townsman, Thomas Shepard, sent to Mather on April 2, 1636, is a page of signatures of 21 men. There is no explanation of what these signatures were attesting to, nor any indication that the page was part of Shepard's letter other than the fact that both were found in the same place. Both Robert and Thomas Deeble are among the names. It has been suggested that these might be the members of the congregation who "importuned" Mather to take over the church. If so, then perhaps Thomas later changed his mind about this.

It is also likely that Robert felt pretty comfortable and established in Dorchester by this time, and, being around the age of 50, an "elder" in those days, he may not have wanted to face the rigors of moving to a wilderness settlement and carving out a new place for himself there. Thomas, in his mid-twenties, may have been a more adventurous soul.

Robert began serving as Bailiff of Dorchester some time in 1637, a post he held probably until some time in 1640. A bailiff, then as now, was responsible for executing decisions of a court of law, but he also typically served as tax collector. In England they were often called "bum bailiffs", because they were said to follow very closely behind people, trying to collect money. Here is Robert's job description, from the Dorchester town records: "he shall levy all fines rates and amercements for the Plantation by impoimding the offenders Goods, and then to deteyne them till satisfaction be made and if the owner of the goods shall not make satisfaction within 9 dayes it shall be lawfull for him to sell the goods and to returne the overplus to the p'ty offending and to be alowed 12d ["d" is short for "pence", a plural form of "penny"] for every distresse and 2d for every impounding of Cow horse or hogg and for every goate a penny and if the sayd Baylif shall be negligent in dischargeing his office and delay the takeing distresse he shall be loyable to a fyne as shall be thought fit by the 20 men [possibly there were 20 selectmen by this time]. It shall be lawful for the sayd Baylif to recover any rates or amercements by way of distresse on any goods."

In 1639 Robert was awarded another acre of land, which extended his home lot "towards the dead swamp", but the town retained rights to any wood on that acre.

But it wasn't until February 7, 1642 that Robert Deeble made his real mark on history. On that day, he and several other townsmen signed a covenant to contribute to the support of a public elementary school. This was the first public elementary school in North America (Boston had the first public school of any kind on the continent; their high school opened in 1630).

Up to this time we haven't said anything about Robert's wife, presumed mother of Thomas. That's because virtually nothing is known of her. "Goody Deeble" ("goody" was short for "goodwife", a common form of address for married women among English Calvinists in those days, equivalent to "Mrs." today; men were called "goodman") did not sign Rev. Mather's covenant until February 12, 1642. Several women did sign the document when it was written in 1636. One possible explanation is that this woman was not Robert's first wife and not the mother of Thomas or any of his other children that we know of. She may have just recently married Robert and joined his church. Thomas' mother may not have come with Robert to New England at all. It is likely that this was because she died, but it is not certain. Divorce was permitted in the Church of England, and "nonconformists" did not regard marriage as a religious matter at all; it was, rather, a civil contract that could be broken, if necessary, without sin.

Nothing more is heard of Robert Deeble after February 1642. It has been speculated that he joined Thomas in Windsor, but his name does not appear in any records of that town or its church. It has also been suggested that he returned to England. There is a burial record for a Robte Deeble in Devon in 1645, but there were plenty of people with that name in that area at the time. The most likely explanation is that he died in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Deaths were frequently not recorded in those days, except for "important people".

So now our story shifts to Windsor, Connecticut.

Thomas of Windsor

The point at which the Farmington River enters the Connecticut was, at the time the first English settlers arrived in New England, inhabited by people whom the Dutch called the Nawaas (probably they were Mohegans). These people called the area Matianuk. By all European accounts friendly and peaceful, they were facing constant harrassment and invasion by the Pequots.

Some time before the arrival of the Europeans, the Mohegans and the Pequots were one nation, but there had been a falling-out and now they were separated, and enemies. Both groups claimed the Connecticut River valley.

As early as 1631, one of the Mohegan leaders, Wahquimacut, made the 160-mile journey to the Massachusetts Bay with a startling offer: if the English would come and settle on the Connecticut River, they would be given all the corn they needed, and 80 beaver skins every year. He issued this invitation in both Boston and Plymouth. It wasn't until later that the English learned that Wahquimacut had an ulterior motive. He figured that the settlers would fight on the side of his people against the Pequots.

Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts Bay was aware of the unstable situation in the Connecticut River valley, and felt it was too dangerous a place for Europeans to settle. But Governor Winslow of Plymouth was enthusiastic about the idea. So a party led by William Holmes of Plymouth sailed around the "corner" of New England, into Long Island Sound, and up the Connecticut River, on a ship carrying materials to build a house, a crew of several men, and some prominent Mohegans who claimed that they had been driven off their land by the Pequots. One of these Native Americans, who sold the land around present-day Windsor to Holmes, was, according to one source, actually a former Pequot "chief" who had been expelled by the tribe and may not have had the right to sell the land.

Holmes' expedition reached a fort on the Connecticut at the site of present-day Hartford, which was occupied by Dutch soldiers and several guns. The soldiers ordered him to stop, but Holmes refused and continued northward up the river to just below the mouth of the Farmington, on the western bank of the Connecticut, where he built his trading post in October 1633.

The Dutch had made a deal with the Pequots for the land around Hartford along the Connecticut River, a plot whose northern boundary probably did not touch the southern boundary of Holmes's location, but they apparently thought this deal made them lords of all they surveyed. So they put together a force of 70 soldiers and showed up at the trading post, guns bristling, banners flapping in the wind. Holmes had built a log palisade around his house and it was manned by his crew. This the Dutch didn't expect. They decided to talk. Holmes pointed out that he had bought the land from what he thought were its original and rightful owners, and claimed that his only intention was peaceful trade. The Dutch withdrew from the trading post, and some four years later, abandoned Connecticut entirely.

By November 1633 smallpox was marching through New England, again, and hitting the native people the hardest, including those in Windsor. A diarist wrote: "This spring, also, those Indians that lived about their trading house there fell sick of the small-pox, and died most miserably; for a sorer disease cannot befall them; they fear it more than the plague. The condition of this people was so lamentable, and they fell down so generally of this disease, as they were (in the end) not able to help one another; no, not to make a fire, nor to fetch a little water to drink, nor any to bury the dead; but would strive as long as they could, and when they could procure no other means to make fire, they would burn the wooden trays, the dishes they ate their meat in, and thier very bows and arrows; and some would crawl out on all fours to get a little water, and sometimes die by the way, and not be able to get in again."

The English settlers braved their own fears of the disease to help them, bringing them wood, food, and water, cooking for them, and burying them when they died, as most of them eventually did.

Meanwhile, some other English entrepreneurs, including Lords Say and Brooke, had been granted a patent to form a colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River (Saybrook) and encompassing points north. Some sources say that the patent did not include the area where the Farmington meets the Connecticut, but their first company of about 20 settlers, under Francis Stiles, arrived at Holmes' trading post at just about the same time as the first group of Dorchester settlers got there, in the summer of 1635. Now, the Dorchester settlers knew about the Saybrook colony, and they also knew there were other Europeans living in the area, but they apparently intended to sit down on lands already claimed by others. Much ugliness ensued.

An agent for the Plymouth Trading Company wrote back to Plymouth to describe the situation: "The Massachusetts men are coming almost daily, some by water and some by land, who are not yet determined where to settle, though some have a great mind to the place we are upon, and which was last bought. Many of them look at that which this river will not afford, except it be at this place which we have, namely to be a great town, and have commodious dwellings for many together. So as [to] what they will do I can not yet resolve you; for [in] this place there is none of them say anything to me, but what I hear from their servants (by whom I perceived their minds). I shall do what I can to withstand them. I hope they will hear reason; as that we were here first, and entered with much difficulty and danger, both in regard of the Dutch and Indians, and bought the land (to your great charge, already disbursed), and have since held here a chargeable possession, and kept the Dutch from further incroaching, which would else long before this day have possessed all, and kept out all others..."

The Dorchester group "drove off" the Stiles party from the specific plot of land where they were setting up camp. They also tried to confine Holmes to a "family lot" containing his trading post, ignoring the fact that he had bought most of the land in the area from the Native Americans. There was a lot of jostling and name-calling and counter-claiming for the next several years, but it seems that the ever-growing influx of Dorchesterites simply overwhelmed the original settlers, who were forced to give way. They even renamed the place Dorchester.

The Pequots continued their raids on the region, so a militia was quickly organized, and it was made illegal to sell weapons or ammunition to Native Americans. The law made no exception for the remaining friendly locals who had survived the smallpox epidemic. In fact, the settlers tended to ignore the evidence before them and distrusted all Native Americans alike.

Connecticut was separated from Massachusetts and became its own colony in March 1636, and on February 21, 1637, the town was renamed Windsor. The land squabbles were gradually settled, with sales made and deeds issued.

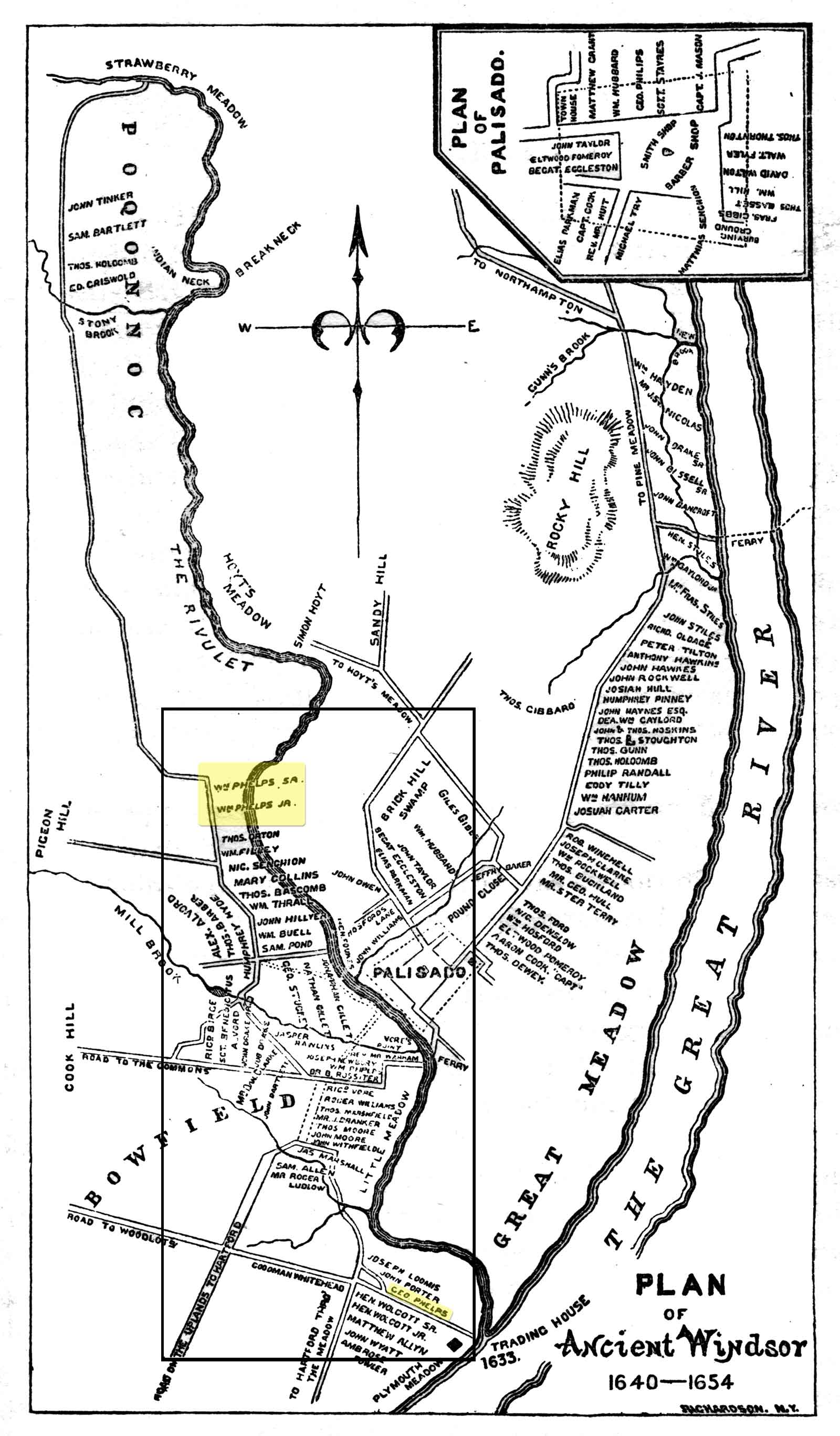

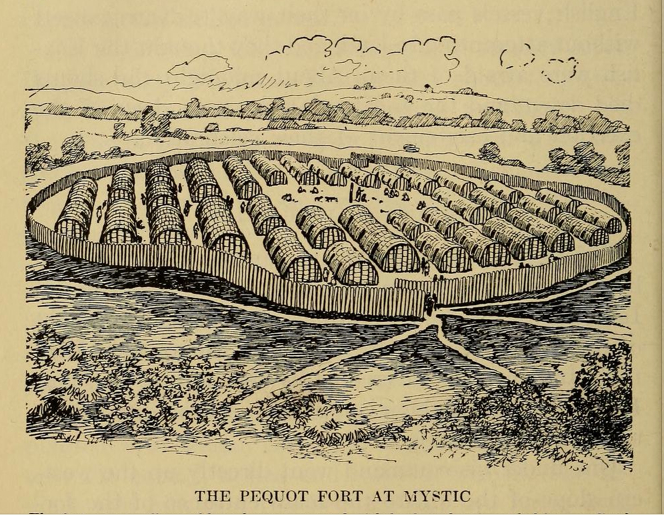

The new settlers established a "Palisado", an area enclosed by large upright log pickets, on the northern bank of the Farmington River, about a half mile northwest of the trading post. Several settlers owned lots inside the walls, but most of them lived outside of it. The idea was to have a refuge during Native American raids.

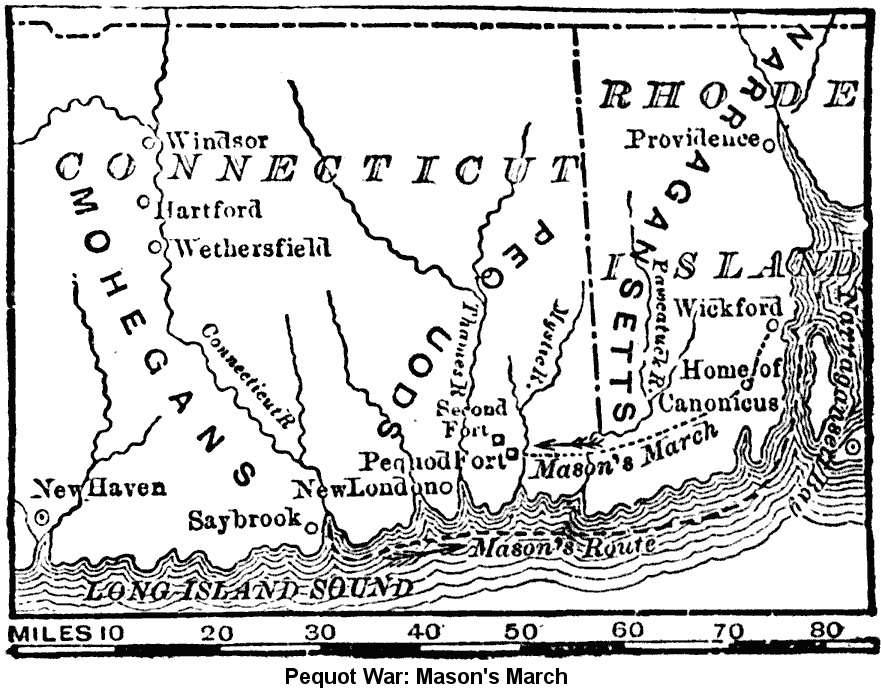

These raids were becoming more frequent. The English settlers in Connecticut valued their peaceful relations with the Mohegans and Narragansetts--also enemies of the Pequots--and, as Wahquimacut had hoped, felt compelled to defend them when attacked. Then, in July 1636, an English trader and much of his crew were attacked and killed on their ship by some Narragansetts near Block Island. This doesn't seem to have been sanctioned by the Narragansett leaders, and when the English came looking to exact revenge, those leaders convinced them that the attackers were being sheltered by the Pequots. Thus began the Pequot War.

The war was short and savage. The English destroyed a Pequot village. The Pequots retaliated by raiding English settlements throughout Connecticut, and they held Saybrook under seige. The settlers assembled a militia regiment under John Mason, allied with a band of Mohegan fighters, in Hartford, and headed for the Pequot village of Msistuck (near present-day Mystic). Meanwhile the local Pequot leader, Sassacus, thought the English militia had retreated to Boston, so he assembled a group of fighters and headed for Hartford to make a raid.

Mason's group picked up a few hundred Narragansetts and a few Niantics (apparently outcasts or rebels, as the Niantics were tributaries of the Pequots) on his way; he had over 400 men when he reached Msistuck. There were only women, children, and old men in the village, Sassacus having taken the younger men with him. Mason set fire to the place, killing most of the inhabitants. Accounts vary for the death toll, ranging between 150 and 500. Mason moved on and destroyed one or two other villages, allegedly also massacring the inhabitants.

The final battle was fought at Sasqua, near present-day Fairfield, in June 1637. Sassacus was on the run, and Mason caught up with him and surrounded his party, which included women and children as well as fighters. He asked Sassacus to surrender; he refused. One account says Mason let the women and children escape; others claim he massacred them along with Sassacus's army.

This ended the Pequots' existence as an organized group for well over 300 years. The Narragansetts and Mohegans divided up their lands. Some of the Pequots were sent to Bermuda or the West Indies as slaves.

The Europeans had stumbled into the middle of a long-running civil war between two Native American factions. They were, to some extent, lured by one of the belligerents and, to some extent, driven by their own lust for land, into taking sides. Although the Pequots were superb fighters, capable of holding a European town under siege for several months, in the end European military technology probably made the difference. No one can justify massacres of innocent noncombatants, but all sides resorted to them, not just the Europeans. After the war the English settlers crowed that God had been on their side, and said, "Let the whole Earth be filled with his glory! Thus the lord was pleased to smite our Enemies in the hinder Parts, and to give us their Land for an inheritance." They probably should have thanked the Chinese, who invented gunpowder, too.

In March of 1639 Windsor was badly flooded, with many houses inundated and two people killed. Despite this disaster, local leaders were able to consider broader matters. In 1639 the inhabitants of Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield met and wrote a constitution for the colony of Connecticut--the first written constitution in North America and, some say, in the world.

In February of 1640, the town's first meeting-house (church building) was finally built.

Thomas Dibble, son of Robert Deeble, was one of the "Massachusetts men" that the Plymouth trading agent wrote home about. He is unlikely to have arrived before the end of the Pequot War, because he made freeman in Dorchester on May 17, 1637. We know he was in Windsor by April 9, 1640, because that's when he made freeman there.

Soon after that, he became well established in the town.

He was most likely a farmer. The passenger list for the Hull company shows him as "husbandm" (husbandman), which was the lowest level of tenant farmer in England. At one point he is recorded as owning four cows, four horses, and five pigs.

His first land in Windsor may have been just southeast of the Palisado, where the Ferry Road met the Farmington River. The lot was 5 1/2 rods (a bit over 30 yards) wide, though we don't know how long, and the records show that Thomas built something on it before 1646, when he sold it. At some point he bought a 3/4 acre lot inside the Palisado, originally owned by William Hubbard, and was living there in 1654.

Thomas was married twice and may have had as many as eight children with his first wife. Who that first wife was is a matter of conjecture, though her name may have been Miriam, and the marriage may have taken place in 1637.

Their children were:

Israel, born August 29, 1637

Samuel, born May 31, 1640, but died young

Ebenezer, baptized September 26, 1641

Hepzibah, baptized December 25, 1642

Samuel, born February 19, 1643, baptized March 24, 1643

Miriam, baptized December 7, 1645

Thomas Jr., born September 3, 1647

Joanna, baptized Februay 1, 1640, but died young

Thomas remained a member in good standing of the church begun by Reverend Warham in Windsor. In 1659 he paid 3 shillings rent to sit in the "short seats" of the meeting house. Many churches from this period had "short seats". They seem to have been pews set facing each other, up front near the pulpit and perhaps perpendicular to the "long seats" further back. They were considered the most prestigious seats in the church.

On November 28, 1661, Thomas' first son, Israel, married Elizabeth Hull in Windsor. Their first recorded child, however, was not born until 1667, a rather unusual circumstance. It is possible that records of earlier children were lost, though it seems unlikely.

At some point his second son, Ebenezer, probably moved to New Haven, CT, nearly 100 miles away on the Sound, because he married Mary Wakefield there on October 27, 1663. But he may have moved back, because, as we shall see, he was in Windsor in 1668.

Thomas' son Samuel married his first wife some time before 1666; her name is unknown. Samuel's daughter with this woman, Abigail, married a man named George Hayes. They are said to be the ancestors of the 19th. President of the United States, "His Fraudulency", Rutherford B. Hayes. Samuel married again, to Hepzibah Bartlett, on January 21, 1668, in Simsbury, Hartford County, CT (just 4 miles west of Windsor).

Thomas's other living children also all married and had children, but since they are not directly concerned with our story, we must leave them here. Hopefully, they didn't give their father as much reason for grief as Israel, Ebenezer, and Samuel did.

The trouble started the day after Samuel's and Hepzibah's wedding. It was cold, the snow was deep, and the newlyweds were visiting Hepzibah's brother Benjamin. It appears that Sam's older brother Israel was also there, as was Benjamin's wife Deborah. Benjamin went out to get some cider for the guests, and while he was out, both Israel and Deborah left the room. When Benjamin came back, he couldn't find his wife, but she came back in shortly with dirt on her coat, and a little while after that, Israel returned, the knees of his pants dirty. When Benjamin asked Deborah where she went, she said she had been to see a Thomas Fowler. Israel said he had been to a neighbor's house.

It wasn't until more than a month later, on March 1, that Benjamin went to court and charged his wife with adultery with Israel Dibble. Israel was picked up by the constable, and Thomas had to come and bail him out, to the tune of 100 pounds. Just based on today's prices (March 2015) for sterling silver, that's over $17,000. But that doesn't really convey how much money this was. One could buy a decent-sized farm, with house and outbuildings, for 100 pounds in mid-17th. century New England. But it's no surprise that the bail was that high; the top penalty for adultery was death (though whipping was more likely).

The records show that Deborah confessed to adultery in court, and Hepzibah claimed that Deborah told her privately that it was true. Samuel and his wife both initially testified that Israel left Benjamin's house, but later recanted and said they only saw him leave the room they were in. Several Dibbles were brought in to testify on Israel's behalf. His sister Miriam said Israel told her that he had gone down cellar to draw some cider from a barrel and had knocked over a dish put under the tap to collect drippings, and that was the "dirt" on his knees. The wealthy Thomas also had to make a second public appearance in court to back up his son Samuel's change of testimony.

There is more to the story, including speculation that Israel actually raped Deborah. But there is no record of a court verdict, and no indication that anything happened to Israel or his marriage as a result. (Indeed, his second child, Thomas, was born on September 16, 1670.) We must assume that, after a good deal of worrying and public humiliation, Thomas Sr. got his 100 pounds back and things went on more or less as usual in Windsor.

Sadly, frequent death was usual in those times. Thomas's first wife died on May 14, 1671. Four years later, Thomas lost one of his sons.

During the early years of European settlement in New England, many Native Americans were able to hold their own among the newcomers by means of land sales and trade in valuable furs. But as time went on and the European population exploded, furs became scarce and the Native Americans were running out of land to sell. Friction between settlers and natives increased, and there were changes in how European courts treated Native Americans. Those whose offenses typically resulted in fines for white settlers were now more frequently whipped. Also, courts began selling Native Americans into slavery instead of allowing them to make financial restitution as they did for European criminals. By the early 1670s, some native leaders were saying that something had to be done about the Europeans, or their people would be wiped out.

The Wampanoags were a federation of several Native American groups who lived in Rhode Island, Connecticut and Massachusetts. One of their top leaders was Metacomet, also known by his legally-awarded English name of Philip. In 1668, the Plymouth colony unilaterally expanded the town of Swansea, on the Rhode Island border, encroaching on land owned by Metacomet and his people. They were forced to sell this land to the English. Relations deteriorated from that point on, and in 1671 Metacomet's people "made a display of their arms to the settlers of the town". This got Metacomet hauled into court and his people were forced to turn over all of their guns.

Metacomet's brother, Wamsutta, seems to have angered Governor Winslow of the Plymouth Colony (not John Winslow, who launched the Windsor trading post, but Josiah Winslow, his son) by selling a piece of land to Roger Williams, the founder of the Rhode Island colony.

Williams had been expelled from the Plymouth colony in 1636 over religious differences, and his subsequent success in Rhode Island apparently still rankled the Plymouth leaders. Governor Winslow had Wamsutta arrested, even though the land sale took place outside the jurisdiction of the Plymouth colony. As Wamsutta was being transported back to Plymouth, his wife tried to rescue him. She was taking him away on a canoe on the Taunton River, so the story goes, but Wamsutta "knew that the end was near", beached his canoe, and died.

Soon after this, Metacomet began negotiating with other Native American groups toward forming an alliance to attack the Europeans. One of Metacomet's advisors was John Sassamon, a Harvard-educated Christian Wampanoag. Their relationship had deteriorated after Sassamon failed to convert Metacomet to Christianity, and he seems to have informed the Plymouth authorities about Metacomet's plans. They hauled Metacomet into court again and threatened him but they didn't have enough evidence to hold him. Sassamon was found dead soon afterward, in December 1674. The court arrested and tried three Wampanoags for the crime before a jury of both European and Native American men. All three were convicted; two were hanged and one was shot, in the spring of 1675. One of them was another of Metacomet's counselors.

Metacomet declared war on the settlers soon after, although there is some dispute as to the precise first cause of what became known as King Philip's War. Some sources cite the trial and hangings. Others say some Wampanoags killed a Swansea settler's cattle and the European retaliated by killing a Native American.

In any event, during the course of the war Metacomet and his allies attacked over 50 of the 90 English settlements in southern New England, burning them to the ground. This does not seem to have included Windsor, though nearby Simsbury was pillaged and then burned in 1676. The settlers mobilized and formed militias. Thomas Dibble's son Ebenezer joined up. History does not record whether any of his brothers also fought.

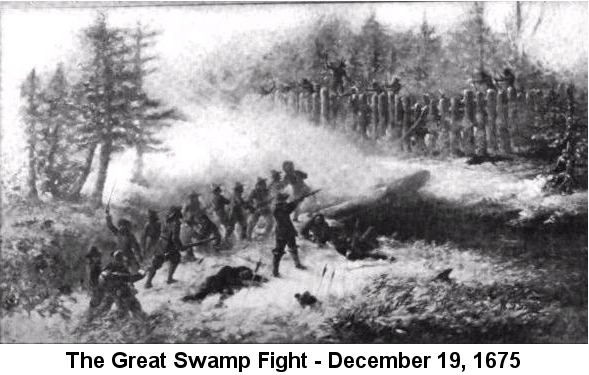

The Narragansetts, who had been squarely on the side of the settlers against the Pequots forty years earlier, were initially neutral in this conflict. However, the settlers claimed they were sheltering some of Metacomet's soldiers and planned a "pre-emptive strike" against them.

On December 19, 1675, militia from Rhode Island, Massachusetts and Connecticut (including Ebenezer Dibble), converged on a Narragansett fort located in a large swamp near present-day South Kingston, Rhode Island. The subsequent battle was known as "The Great Swamp Fight". The fighting was indeed fierce, and Ebenezer was killed. But eventually the fort was overrun and burned, along with most of the winter stores of the Narragansetts. Women and children in the fort were killed or evicted. This was the culminating act that led the Narragansetts to join Metacomet's Wampanoags in the war.

The high tide for Metacomet's armies came in March 1676, when they attacked Plymouth and burned Providence, Rhode Island to the ground. Thereafter the tide turned. The Wampanoags lost more battles than they won, and Metacomet's allies began to desert him. Metacomet was tracked down and killed at Mt. Hope, in the swamps south of Providence, by Plymouth militia in early July. His dead body was then beheaded and drawn and quartered--signifying that the settlers considered him a criminal, and not a worthy foe in battle. His head was kept on display in Plymouth for 20 years.

The war largely ended with Metacomet's death, although some isolated raids occurred in northern New England for a while longer.

History records that Ebenezer's father Thomas took inventory of Ebenezer's worldly goods as part of the probate process of his will, a duty he performed conscientiously for many members of the community (including Matthew Grant, the famous diarist and compiler of church records). Ebenezer's estate was valued at 65 pounds, 5 shillings, and this was not enough to cover his debts, as his estate was ruled "insolvent". Someone named Mr. Jones, of New Haven, CT (perhaps a soldier with whom Ebenezer served?), wrote to Governor Leete on behalf of Ebenezer's widow: "Sir I pray be pleased what you can do to favor and further the bearer, Wid. Dibble, that her husband's Estate may be settled. He was killed at the Swamp Fight; died in debt more than his estate. T'were a work of mercy to consider the poor widow and fatherless children."

Not long after Ebenezer's death, nor long before that of Metacomet, Ebenezer's older brother Israel's fourth child, George, was born, on January 25, 1675. Of him, much more, later.

Thomas, the patriarch, married his second wife, Elizabeth Hinsdale of Hadley, CT, on June 25, 1683. This was her third marriage. The previous two had not necessarily left her widowed. There is a story that, "in 1674 she was living apart from [Hinsdale] and was summoned by the court, but appears to have gotten off without any penalty, refusing to answer, but Hinsdale was whipped and fined."

Thomas and Elizabeth had no children, and she died relatively soon, on September 25, 1689.

Thomas lived on, witnessing wills and land sales, taking inventory of estates, and behaving generally as a respected pillar of the community, until the new century arrived. He passed away on October 17, 1700, some 83 years old. In his will, he awarded the north half of his orchard to his son Samuel, "where he lives". and to Samuel's son Samuel Jr. after him. Perhaps this was the orchard through whose deep snow Israel claimed to have tramped to get some cider more than 30 years earlier. Thomas gave the south half of the orchard to his son, Thomas Jr. and to his grandson Abraham after him. He gave a 2-acre meadow to his daughter Miriam. The remainder of his estate was divided between his sons Samuel and Thomas, and to his grandsons Josias (son of Israel) and Wakefield (son of Ebenezer). Despite all of this land and other worldly goods, Thomas's estate was valued at only 60 pounds, 14 shillings, 1 pence. This total might have been made after settling his debts. It might also be an indicator of just how much one pound sterling was worth at the turn of the 18th. century.

Israel was not included in the will, which was written in 1699, because he died in December of 1697. The other sons of Israel, Thomas and George, may not have been mentioned in the will along with Josias because they had left Windsor for Long Island, New York. And there we must follow them now.

George of East Hampton

The earliest reference to a Dibble in East Hampton, Suffolk County, NY, is March 27, 1697, when George witnessed a land sale. The next reference is the marriage of Thomas Dibble to Rachel Mulford on April 2, 1699. (This Thomas was the son of George's father Israel's younger brother Thomas--in other words, George's cousin, not his older brother.) Officiating was the Reverend Nathanial Huntting. The names Thomas and George both appear in an undated "table of persons engaged in the mechanic arts" in A History of the Town of East-Hampton, N.Y., by Henry Parsons Hedges. Hedges presented the table as part of a discussion of the expansion of local manufactures at the "commencement of the 18th century". "Geo. Dibble" is listed as a weaver. Thomas is listed as both a cooper and a weaver (although there was a Thomas Dibell of "Sea brook" CT, living not far away in Southold, Long Island, who was a cooper). (See Problems in Linking John Dibble of Sanford Township Broome County NY to Robert Deeble for further discussion of the "Thomas problem".)

On March 22, 1703, George, age 28, bought a quarter-acre lot in the village of East Hampton from James Barber for the princely sum of 11 pounds, 10 shillings. Even then, the Hamptons were prime real estate! George must have been a very prosperous weaver indeed.

And he was ready to settle down. On December 28, 1703, he married Mary Buil.

Sadly, their happiness was short lived. On January 8, 1706, Rev. Huntting recorded, "The wife of George Dibble, having lain in abt. 3 weeks, sitting up & finely well, was taken & died in about a quarter of an hour, died about 11 in ye morning, taken first cold in one foot." She was buried in the East Hampton village cemetery.

The expression "lying in" is an archaic term for childbirth. If Mary had "lain in" for three weeks, she probably was pregnant and having complications. So it's possible that she left behind a newborn child.

And this may have been the reason that George got married again, perhaps, astoundingly, just a few days later, to a woman named Abigail.

Actually, it's not so astounding. Mortality rates were very high generally; if people vowed to remain married "til death do us part", they did so in full knowledge that the parting would be likely to come soon. Actually, while the phrase "til death do us part" can be traced back to the 11th. century in England, it was part of the Roman Catholic marriage ceremony and later included in the Church of England Book of Common Prayer. The more radical "dissenters" among the Puritans disdained that Book, and among them, marriages were typically civil contracts, not religious ones, and love was not necessarily an important consideration. Marriages were more utilitarian in nature. So it wasn't unusual for men with young children to remarry very quickly--extremely quickly, in fact--after the death of a wife. It was strongly felt that only a woman was suitable to raise young children in those days. According to various historians, "the first marriage recorded in Plymouth was between a widower of 7 weeks and a widow of 12 weeks; a New Hampshire governor married a woman who had been widowed for only 10 days; and Isaac Winslow is reported to have proposed to a woman on the same day he buried his wife."

We know that George was in East Hampton in 1708, because he witnessed a land sale there in July of that year. But there is nothing more on him until Rev. Huntting baptised his son Jonathan on October 28, 1711.

From Robert Deeble to Jonathan Dibble, the road is long, winding, and pitted. In some places the bridges have been washed out and we can only imagine, through conjecture, where they once may have stood. But we have arrived at our destination, and so we return you now to those thrilling days of yesteryear (well, somewhat later yesteryear), back on the main page.