Somewhere west of the River Vistula, near the little church village of Radziwie, in the year 1800, a child was born to Katrzyna Flak. She and her husband Jan named him Michal. If Michal was baptized a Catholic, it was probably in St. Benedict's Church in Radziwie, some version of which had stood in the town since the 11th. century (its current building, erected in 1902, still stands there today).

This was historical Poland, but it was a Poland that was no longer independent, and that fact bore directly on the actions of the first members of this family to come to the United States.

The region had been part of a much larger nation, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, that had stood for centuries. In 1791 the Commonwealth became part of a small vanguard of liberalizing nations. It enacted a new Constitution that established the King as a constitutional monarch, answerable to an elected legislature and a separate judiciary. Many other liberal reforms were also introduced. This frightened and angered the nation's autocratic neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and Austria, and they invaded the Commonwealth and broke it up. By 1793, seven years before Michal was born, the Flaks' home was in a part of the German kingdom of Prussia called South Prussia.

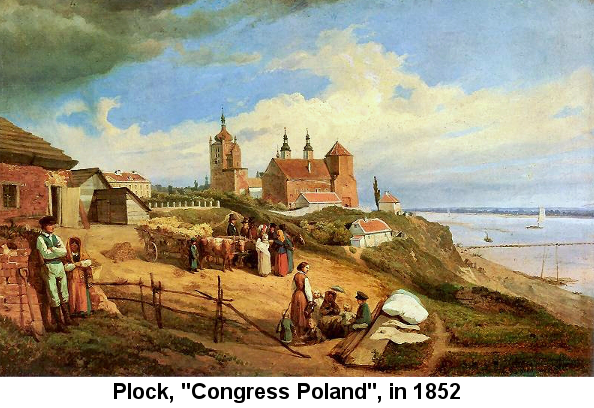

In the early 19th. century this was very rural country, broad flatlands covered in a patchwork of small farms and pine forests, punctuated by little lakes. The nearest city was Plock, just on the other side of the Vistula. It had finally recovered from its last disaster, destruction by the Swedes a few decades before. It was the seat of the provincial government at the time (Polish province names and boundaries have changed many times over the centuries), and served as a port for river barges carrying the grain that was the principal crop of the region. Still, it was a very small city. Jan Flak may have been a farmer (perhaps a serf at the time of Michal Flak's birth), or he could have been a craftsman or merchant in town. We just don't know.

In fact, we don't really know anything about the early Flak family.

Members of that family obviously moved from place to place, but if any of them were serfs, then prior to 1810 in Prussia, or to Tsar Alexander II's decision to "free" the serfs in 1861 in the Russian Empire, they either would have had to get permission from the landlord to move, or they would have had to run away. Runaway serfs were not unusual, and many were hunted down and captured while others succeeded in escaping to different locations.

We know even less about Jan's son Michal than we know about Jan--only that he married a woman named Bogumila Artechowska, and they had a son named Stanislaw Flak.

Stanislaw married Jozefa Liziewska in 1863 in Stoczek, Wegrowski Parish. Jozefa's parents were Jozef Liziewska and Marcjanna Oldak. These families, like the Flaks, may have been Jewish, Catholic or Protestant.

Stoczek is about 80 miles due east of Radziwie, near the border between what were then Warszawa and Siedlce Provinces. It's about 12 miles south of the Bug River (and about the same distance south-southwest of Treblinka, where a Nazi extermination camp stood during WW II), in another flat region of small farms and forests, one even more rural and isolated than Radziwie.

Stanislaw's and Jozefa's marriage there took place in one of the most turbulent and dangerous years of Poland's 19th. century history.

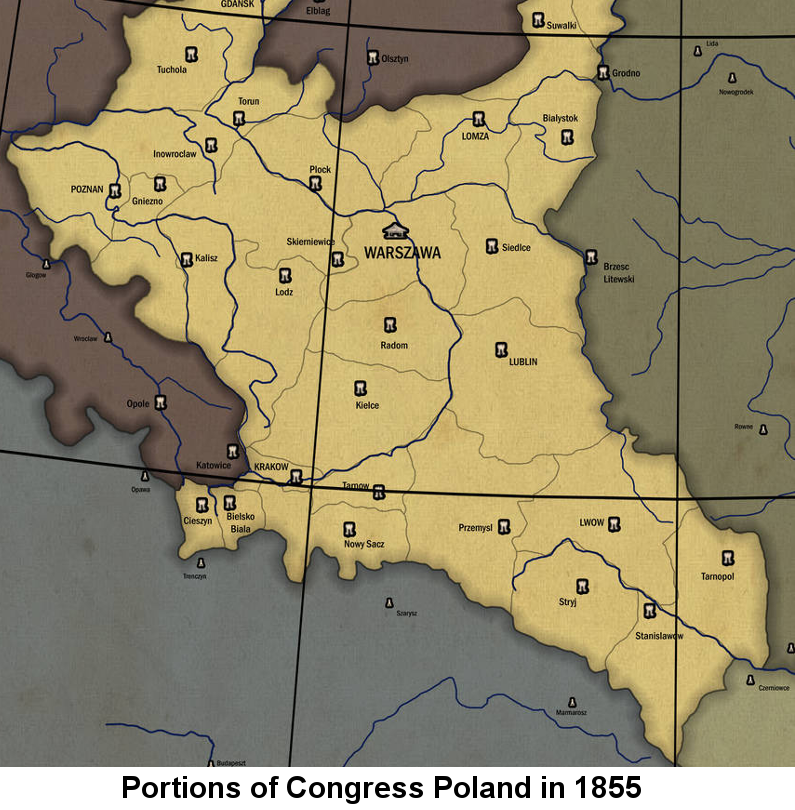

The Poles had never really accepted the partition of their country in the previous century. At that time sections of their land were handed over to Prussia, Austria, and Russia. Soon after that, Napoleon invaded Prussia and points east on his way to Moscow, raising the hopes of the Poles that they might recover their kingdom. They revolted, but when the dust cleared, control of what had once been Poland was placed in the hands of Napoleon's various German client states. Then, following Napoleon's final defeat, the Congress of Vienna was convened in 1815 among the major European powers to sort out the mess and re-establish borders. The Congress awarded most of the Polish lands given to both Prussia and Russia in the 1700s--the area where our families lived--to Russia, and the area became known as "Congress Poland". Since then, there had been several cycles of revolt and repression in the region, each ending in further loss of what little autonomy the Poles still had. The last major one had begun in November 1830, and coincidentally involved a big battle against the Russian army in another village called Stoczek--"Stoczek Lukowski", about 60 miles south of our Stoczek, or "Stoczek Wegrowski".

By the 1850s pro-independence sentiments were on the rise again. A new Russian Tsar, Alexander II, was crowned in 1855, and he began to follow a liberal course. The urban middle class and Polish nobility resumed talking about trying to regain some of the autonomy that was lost after the 1830-31 uprising. In 1859-60, Italian puppet states controlled by France gained their independence and joined to form the Kingdom of Italy, inspiring a younger generation of Polish activists. Meanwhile, eastward in Russia proper, Alexander's army had been weakened after the loss of the Crimean War, but he continued to liberalize Russian society, freeing the serfs in 1861, making it easier for industrial corporations to form, supporting the development of railroads, and introducing reforms to the army.

However, Alexander's top adminstrator in Poland, Alexander Wielopolski, was no fan of the Tsar who bore his name, and he looked askance on his reforms. He had his ear to the ground and was aware of the growing agitation for independence. By the early 1860s organized groups were staging protest marches, some of which were ended violently by the Russian army. This led to underground organizations developing secret plans for revolt, to begin in the spring of 1863. Determined to head off trouble, Wielopolski announced that all young Polish men were to be conscripted into the Russian army for a term of 20 years, beginning in mid-January of that year. This led the conspirators to move their plans up to the night of January 22. Thus began the January Uprising, the largest and most widespread Polish revolt since the partition. Eventually it spread to the lands under German and Austrian control as well, but our concern is for Stanislaw Flak and Jozefa Liziewska, who got married right in the middle of it. There were battles just ten miles away, near Wegrow, on February 3 and May 10.

We don't know how old Stanislaw was at the time or what his occupation was. He may have been too old to be targeted for Wielopolski's conscription campaign. Did he know that there was a "secret" Polish government setting itself up in Lithuania (also formerly part of the ancient Polish state, and in 1863 part of the Russian empire)? Was he aware that among the organizers of the uprising there were "Reds", who favored immediate independence by force, and "Whites", who initially had supported peaceful reform efforts to gradually gain more autonomy? (After the Russian army moved in to repress the uprising the Whites joined forces with the Reds.) He certainly could not have been unaware of the turmoil and violence going on around him, but he may have been too busy courting Jozefa, and perhaps adjusting to life as a newly freed serf, to care very much.

Although the serfs were "freed", they weren't entirely free to own real estate. The deal that Tsar Alexander II negotiated with the wealthy landlords to whom the serfs owed service was that the land would be divided into "communes" (no, they were not invented by the Bolsheviks, who organized them differently), each of which was "owned" jointly by some number of freed male serfs, now called peasants, and those peasants would be heavily taxed to pay off the landlords for the loss of the land--so-called "redemption payments" that continued for 49 years. This was somewhat similar to the debt peonage experienced by black sharecroppers in the American south after the Civil War. In Russia and Poland, this system seems to have gradually faded out on an informal basis. Although the freed people were not supposed to be allowed to sell the land or migrate to the cities, the labor demands of growing industrialization proved decisive. Poland was industrializing even faster than Russia, and many peasants moved to the cities to work in factories. They may have somehow gotten around the rules and sold their shares of the communes to those who remained behind. Many of those still on the land thus became rather wealthy landowners themselves.

When the uprising ended in 1864 with yet another Polish loss, the repression that followed was worse than any that had come before. Many of the young men were indeed conscripted into the Russian army. Some 70,000 were imprisoned or exiled to Siberia. Around 2000 were executed. All pretensions of there being a separate Poland were dropped; the region became just another Russian province, where use of the Polish language by government agencies or in schools was forbidden. By the early 1880s, even the name of "Poland" was being extinguished; instead, the Imperial Russian government began calling the region "Vistula Land".

These circumstances did not lead Stanislaw Flak to migrate to the big city. Instead, he settled a couple of miles southwest of tiny Stoczek, in the really tiny hamlet of Zgrzebichy. There, on December 24, 1878, Stanislaw's and Jozefa's son Sczepan Flak was born. Sczepan was their sixth child. The others were:

Julianna - born 1865 in Stoczek

Weronika - born 1866 in Stoczek

Wladyslaw - born 1868 in Stoczek

Jan - born 1871 in Stoczek

Feliks - born 1874 in Ludwinow

Mateusz - born 1879 in Stoczek

Karol - born 1883 in Stoczek

(Probably all but one of those birthplaces were actually Zgrzebichy. Stoczek is where the parish church that kept the records was. Feliks' birth in Ludwinov is probably not significant. There are almost two dozen places in Poland called Ludwinov. One of them is only about seven miles away from Zgrzbichy. Perhaps Jozefa was caught short while visiting, or maybe she traveled to meet a midwife.)

Today, Zgrzbichy is a tidy, well-kept, charming little rural hamlet surrounded by broad flat fields and small woodlots. We can only imagine that in the 1880s and 90s it was rather dustier, shabbier, and poorer, than it appears today. We can also imagine Sczepan as a compact, wiry, headstrong young man bored with his surroundings and eager to take his chances in the booming industrial city of Warsaw. In any event, that is where we find him during the next dangerous upheaval in Polish history.

Sczepan may have come to Warsaw seeking work and excitement in his early 20s, around 1900 or so. He could have found work as a laborer in any of a number of machine shops or factories, in construction, or perhaps with a railroad. He likely would have belonged to an industrial union. But times soon turned sour. A recession hit the Russian Empire in 1901 and continued to 1903. Then the Empire got involved in an ill-advised competition with Japan for influence and territorial control in Korea and China. In 1904 this erupted into the Russo-Japanese War, which Russia lost. That led to another major wave of unemployment, and over 100,000 Polish workers lost their jobs--that is, those workers who had not been conscripted into the army to fight the Japanese. Sczepan was proably not among those conscripts (though his younger brother Karol was), because his son Casimir was born on March 4, 1905, in Warsaw. Most fighting in the war ended by June of that year.

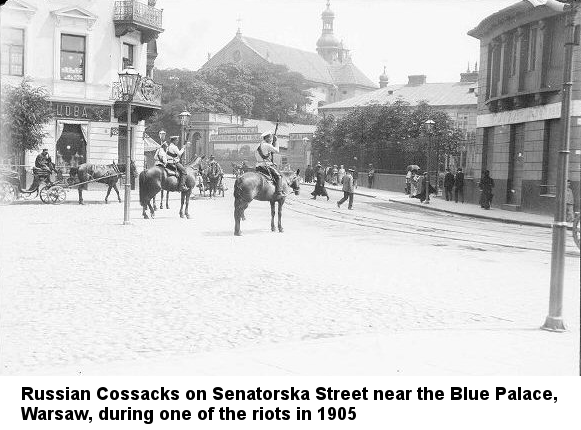

But the fighting inside the empire had just begun. A wave of industrial strikes began in 1904; by January 1905 over 400,000 Polish workers were on strike. A large mass of workers tried to reach the Tsar's palace in St. Petersburg, then the capital of the Russian Empire, in January; they were fired on by soldiers against orders to let them pass. This event was known as Bloody Sunday and is considered the start of the (abortive) 1905 Russian Revolution. A couple of weeks later over 100 workers were shot in the streets of Warsaw. At one point more than 93% of Polish industrial workers were on strike. The "Lodz Insurrection" took place in June; it resulted in several days of street fighting between workers and the Russian army, leading to over 2000 casualties, including more than 100 civilians killed, in the industrial city of Lodz, about 60 miles southwest of Warsaw. There were strikes and protests in other major Polish cities throughout 1905. The Russians also tried to divert the Poles by inciting anti-Jewish pogroms in various locations, including in Siedlce, about 25 miles southeast of Stoczek, in September 1906, where 25 Jews were killed and hundreds injured. The Russians tried to blame the event on Polish "revolutionaries" but all evidence indicates that the murders were committed by Russian soldiers and that Christian Poles tried to protect the Jews (who constituted a majority in the town).

In Russia proper, the revolution forced the Tsar to make concessions, including establishment of the Duma, the country's first legislature. In Poland, though, the only result was more oppression. Scattered protests, violently broken up by Russian troops, continued for the next two years. Conscription was stepped up as punishment for striking workers.

It's not clear at all where Sczepan was or what he was doing during this violent period, though we would have to assume that as an industrial worker, he was on strike part of the time.

According to the best available records, he married Julianna Wachowicz in 1907 in Brzoza Parish, about 60 miles south-southeast of Warsaw. She apparently died quite soon afterwards, because he married Marianna Banaszek in 1908 in Postoliska Parish, about 25 miles northeast of Warsaw. Marianna was born in 1888 in Postoliska to Jan Banaszek and Anna Kostrzewa. Jan Banaszek may have been born in 1845 in Postoliska, with parents Michal Banaszek and Marianna Konska. Jan and Anna were married in 1867 in Postoliska; her parents were Jan Kostrzewa and Marcjanna Dziuglowska. Some family members had heard that Marianna may have been a "Gypsy".

Sczepan and Marianna's daughter Antonia was born on May 1, 1909 in Warsaw. Their son Waclaw was born on January 30, 1911 or 1912 in that city.

At some point after Waclaw's birth, Sczepan became dissatisfied with life in "Vistula Land", and felt it was necessary to leave, quickly and somewhat surreptitiously. The reason he later gave his family was that he was "tired of eating rats in the Russian army", but there may be other explanations.

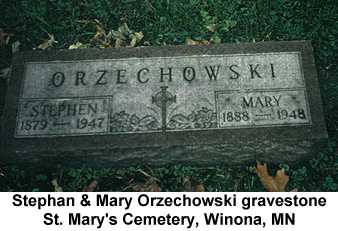

At any rate, Sczepan boarded the ship George Washington in Bremen, Germany in early May of 1913 under the name Szapan Flakewitz (as recorded by the English-speaking crew), and he arrived a few days later at Ellis Island in New York City. It is there that the family believes he decided to change his name to Stephan Orzechowski, supposedly to further throw off any Russian authorities who might have been trying to track him down.

Orzechowski was the name of a very famous and controversial Polish priest of the 16th. century: Stanislaw Orzechowski, who came from a noble family and was excommunicated for challenging the Catholic church's rule of celibacy for priests. He was a rake as a young man who said that he "had many places to lie down", but he chose to clean up his life and get married. This the Pope would not tolerate. But the defrocked priest continued to publish pamphlets criticzing the Pope and the church, and eventually they decided they preferred him to use his pen for them rather than against them, so he was reinstated--though the church never acknowledged his marriage. He was also known for defending Polish nationalism prior to the establishment of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Family members have said that Stephan chose "Orzechowski" because it was a common Polish name--which it is. However, some family members also heard talk that perhaps Stephan was descended from the landed nobility, a notion that may have come from Stanislaw Orzechowski's ancestry. Stephan the unlettered industrial laborer from Warsaw may indeed have picked the name because it was not unusual. But if Stephan was a revolutionary on the run, he may have chosen "Orzechowski" for its nationalist connotations. Who knows? Certainly his family did not, but it was a source of hushed conversations among the men, after shooing the women away, about "whites" and "reds" and other mysterious things.

We do know that from Ellis Island he journeyed to Winona, Minnesota, where he planned to meet someone with an address on East King St. The name is unreadable on the ship's passenger list. But another man on the ship, Josef Koslowski, was also headed for the same address, to meet someone with a different, also unreadable, name. Sczepan's wife Marianne (later known as "Mary", using a surname variously spelled as "Flaik", "Flack" and "Flak" came, with Casimir, Waclaw (known as Vincent and sometimes as "Fritz"), and Antonia (now called Angeline), and, perhaps, Sczepan's brother Feliks, to New Brunswick, Canada, in 1914.

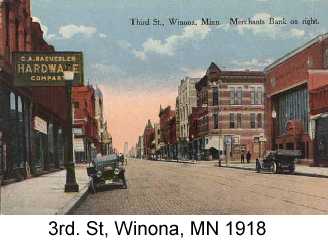

Why Winona, Minnesota, of all places? It may be as simple as the fact that a lot of Poles had settled there in the late 19th. century; by 1900 they made up a quarter of the city's population. The local Polish historical societies make much of the fact that many of those settlers were Kashubians, a linguistically and culturally distinct Slavic ethnic group closely related to the Poles. The Kashubians are celebrated as the founders of St. Stan's church, among other things. But Sczepan and his family most likely were not Kashubian; the Kashubians historically hailed from what used to be a part of Prussia called Pomerania--significantly further west and north of Sczepan's birthplace, and even Plock and Radziwie, though closer, fall outside historic Kashubia. In the big city of Warsaw--also well east of Kashubia--Sczepan would have met people from other parts of the region, including Kashubians, who had relatives who were building successful lives in Winona. Certainly lots of people were; according to Minnesota: A State Guide (one of the famous WPA state guidebooks), at one time Winona had more millionaires than any other city of its size in the United States.

The city was founded in 1852 on the site of a Dakota village called Keoxa. The region was part of a vast swath of land that the Dakotas were forced to cede to the United States in 1851. The place was a promising location for both milling and shipping on the Mississippi River, on marshy ground about 50 miles downstream from Red Wing and nearby Cannon Falls, where the first Dibbles would arrive just a couple of years later. Lumber was its first big industry, and the town had as many as 10 sawmills at one point. When steamboat traffic on the river became a regular thing, Winona became a port for the abundant wheat shipments coming from the farms of southeastern Minnesota. Later the railroad came to carry the same types of goods, and the good transportation options made it an excellent location for a variety of manufacturing companies. By 1913, the city had over 18,000 people.

Stephan, now known as "Steve", probably started out working in those factories. During that time Steve and Marianna's (now known as "Mary") first American child, Stanley "Puck" Orzechowski was born, on January 19, 1916.

On September 10, 1917, Steve signed on at the Chicago & North Western Railway Company as a "pit man". Before the use of the "road switcher" design, railroad locomotives needed to change direction so as always to be pulling a train of cars. This was done in a railroad yard with a turntable. A railroad turntable is a length of track set on a bridge-like structure that rotates within a circular pit. The locomotive was detached from its train and run onto the turntable bridge, and then the bridge was rotated until the locomotive faced in the desired direction. Early turntables had to be pushed by men standing in the pit but by the early 20th. century most turntables were rotated by steam or hydraulic power. The turntable had to be locked in place before the locomotive ran onto it, and then unlocked before it was rotated, then relocked while the locomotive moved away. Steam locomotives weren't always well-behaved on the turntable; leaky brakes or valves could cause them to move on their own and fall into the pit. A pit man was responsible for locking and unlocking the turntable and keeping a close eye on the movement to warn against accidents.

On July 6, 1918, Steve and Mary's twin daughters Cecelia "Ceila" P. and Opal Orzechowski were born. Soon afterwards, Steve resigned his job at the C&NW and went to work for the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company. That September, when he rather belatedly registered for the World War I draft, he was working across the river in Trempeleau County, WI, helping to pour concrete for a railroad bridge. Perhaps the CBQ paid better wages, or maybe he didn't get along with his boss at the C&NW.

Or maybe the reverse was true, because he returned to the C&NW on January 11, 1919. For most of his time there he was a "stationary fireman", working around steam boilers that were not locomotives but rather provided heat to shop buildings or power to devices like turntables or various types of heavy machinery in repair shops. The most common activity of a "fireman" was shoveling coal into the boiler's firebox, but the term came to apply to a variety of boiler-related jobs.

Steve seems to have made a pretty good living at these jobs. He purchased a house at 771 East Front Street, between High Forest Street and Manakto Avenue. The tracks of the railroad for which he worked paralleled the street across from the house's front windows. Beyond that, some distance away, was the river.

Another child came: Sophie Orzechowski was born on October 27, 1919.

In October of 1921, Steve submitted a "Declaration of Intention" to become a US citizen. As required, he declared that he was neither an anarchist nor a polygamist--not even a "believer in the practice of polygamy"--and he forever renounced allegiance to the "Government of the Republic of Finland". This is not likely to have been a deliberate attempt to keep his origins secret, since on the same form he reported that he came from "Russia". But the error appeared on both handwritten (not Steve's handwriting) and typewritten versions of the declaration form, a fact that was to haunt him.

From July 3 to September 18 of 1922, Steve was out of work due to what the C&NW called "labor trouble". During World War I, the railroads were effectively nationalized by the US government in the interest of ensuring reliable transport of soldiers and munitions. Wages rose during that period. In 1920 control of most aspects of railroad operation was returned to the private sector. Wages, though, remained governed by a new Railroad Labor Board, which began cutting them. In 1922 the Board approved average cuts of 12% for maintenance workers like Steve Orzechowski. Several railroad unions, including the so-called "Big Four", negotiated deals with the railroad companies that blocked these cuts, but not all unionized workers were protected. The unions had other grievances as well, such as a growing practice of contracting out shop work to non-union companies. Steve was probably a member of the International Brotherhood of Stationary Firemen and Oilers, which does not seem to have been privy to the Big Four deal. The resulting nationwide strike of over 400,000 workers was known as the Railroad Shopmen's Strike of 1922. It was largely a failure for the workers, who returned to work at the reduced wages that started the trouble. Many if not most of the striking workers, including Steve, were treated as new employees when they came back to work, losing any seniority rights and previously-vested pensions. In Steve's case, he was over the age of 35 when the strike ended and so was required to "waive" rights to a retirement pension that he probably had when the strike began.

Not long after the strike ended, the twins Joseph and Stella Orzechowski were born, on December 2, 1922. That happy occasion was forever marred a few weeks later, just after Christmas, when little Opal died at the age of 4 1/2, on December 27.

In November of 1924, Steve tried again to declare his intent to become a citizen. This time he renounced his citizenship to the "Present Government of Russia". Then, in April 1925, he took the next step: he filed a petition to be "naturalized". However his petition was dismissed because his original declaration of intent had him renouncing allegiance to Finland. The explanatory note stated that the erronous declaration was attached--but what was actually attached was an earlier petition, filed the previous November, in which Steve renounced allegiance to the "Republic of Poland"--of which he had never been a citizen, because that country only came into existence after the end of World War I. This snafu did not get finally sorted out until much later.

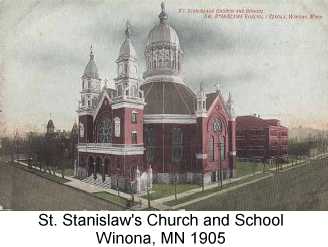

The family were members of St. Stanislaw's Polish Catholic Church, known as "St. Stan's", where services were held in Polish. The younger children went to St. Stan's Catholic elementary school about 5 blocks from the house, but they did not go to high school at a time when most of their peers in Winona--even those who lived in poverty--would have gotten a high school education. Instead, they went to work, sons and daughters both.

Steve's oldest son Casimir (his name also appears as "Kasmir" and "Casmir" in various records) worked as a "brusher" at the Foot Schulze shoe factory in 1923. The following year saw him working for Thomas Hammer as a mechanic; Hammer may have been running an auto repair shop at the time. On July 1, 1926, the young man, having just turned 21, went to work with his father at the C&NW railroad. He started out at as a laborer in the "car shops"--where railroad cars were repaired. He moved up to "fireman" like his dad. By 1934 he was doing similar work at Bay State Milling.

Steve and Mary's second son Vincent reached working age in the early 1930s, but we don't know where he worked.

Mary, and later Angeline, and much later, the other girls, cleaned the houses of the wealthier people in town, and were paid in cash, clothing, household items, and sometimes, medical treatment.

Throughout his life in Winona, Steve was known for having a bad temper, and he was especially difficult to get along with when things weren't going well. Family members tried to keep him from finding out if one of the children was in trouble, presumably to protect them from a beating. He was known to throw his lunch bucket if he didn't like what it contained, and some members of the family took to calling him "Joe Stalin." It may have been worse than that. On September 24, 1929, the Winona Republican-Herald reported that his wife charged him in court with "threatening to assault her". He pleaded guilty and forked over $50 as a pledge for a "peace bond ... in which he promises to keep the peace toward all the people of Minnesota and especially Mrs. Mary Orzechowski for a period of six months."

Angeline was described as a young adult as a "flapper" who was determined to shed her Slavic heritage and be a thoroughgoing American. She refused to speak Polish or talk about the old country. Based on her later life, she may either have endured a number of traumatic experiences, and/or began to develop an anxiety disorder during this period.

The family recalls that Casimir, in contrast to Angeline, resented Steve's decision to change the family name. At some point in the 1940s he made a decision to change it back, and from that point on he was known as Casimir Flak.

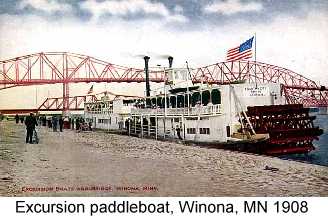

Steve and Mary's daughter Celia made homemade beer in the cellar and rolled cigarettes for him. Later their granddaughter, Gladys, continued the cigarette-rolling tradition. For entertainment, the children went to dances or took paddleboat rides on the Mississippi.

On September 9, 1935, at the age of 57, Steve Orzechowski was "dismissed" from the C&NW "for cause". The 1940 US census recorded him as unemployed and "unable to work". So he may have been injured on the job and fired. Or his ongoing attitude problems may have finally caught up with him.

We'll return to the Orzechowski family, as well as to all of our other families, in the next section. Stay tuned.